Newark homicide detectives call it “the bible.”

The Star-Ledger, June 19, 2006

There is a book on the shelves of Newark’s homicide squad that tells the never-ending story of murder in the city.

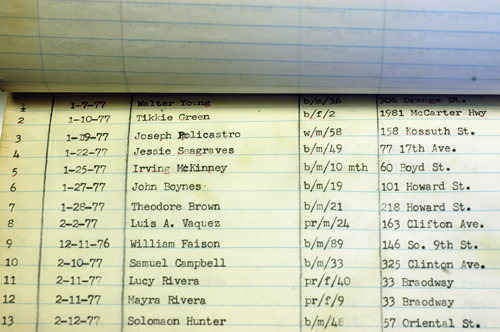

The ledger, about the size of a pizza box, lists every known Newark killing since 1929. From the cracked and yellow pages of the early 20th century to the freshly printed entries of the 21st, each typewritten line contains the same bare facts for each case: date, victim, age, address, suspect, weapon, file number.

In an age of digital databases and online search engines, this old formula remains a proud tradition among Newark homicide detectives, who call it “the bible.”

To the detectives, the dusty book remains the only way to look up pre-database cases - old mob wars, race riots, gang battles, husband-wife attacks, murdered babies, and thousands of other deaths. But it is more than a catalogue of killings. It also documents the city’s changing culture and population. And for some people, it helps solve the mystery of lost relatives or interrupted family trees.

“Just think of all these people who have died in one city, all the years of sorrow and hard work,” said Thomas O’Reilly, a retired chief and unofficial Newark Police Department historian. “The book is like a memorial to the deaths, and the efforts to bring the killer to justice.”

Anyone looking through the bible eventually stops at Oct. 23, 1935, the day legendary mobster Dutch Schultz and three of his lieutenants were gunned down at the Palace Chop Shop on East Park Street.

Schultz’s rubout has been dramatized in dozens of novels, articles and movies, including “Billy Bathgate” and “The Cotton Club.” But in the homicide book, he’s listed only as Arthur Fleigheimer of the Robert Treat Hotel. The only mark that makes the entry stand out is a handwritten note that says, “Bugsy Workman did time for this,” a reference to triggerman Charles “The Bug” Workman, who spent 23 years in jail for the crime. The other gunmen were never found.

Flip to the pages beginning with July 14, 1967, and there is a long list of people, described as “riot victim.” The entries mark the darkest period of Newark’s history - six days of looting, fires and gunbattles that left 23 people dead, most of them black.

The first riot victim listed is Rufus Council, an itinerant laborer who was shot in the head while standing outside a restaurant on South Orange Avenue at 5:30 p.m. on July 14. Council wasn’t actually the first person killed; it was James Saunders, shot by police at 4:10 a.m. the same day.

Right under Council is the youngest riot victim, Edwin Moss, 10, hit by gunfire as he sat in his family’s car. A few lines down are Newark Police Officer Frederick Toto and Newark Fire Capt. Michael Moran, the only public safety workers killed during the riots, both by sniper fire.

None of the riot entries names any suspects.

But most entries aren’t as historically significant as the Schultz murder or the riot. They are people long forgotten.

No one knows that better than Newark Police Detective Rashid Sabur, who investigates cold cases, usually after receiving tips from other officers, prosecutors or a victim’s relative. His search for killers always starts with the book.

“Without that book, you have a hard time finding old files,” Sabur said. “It’s a map to the dig.”

Over the years, Sabur has repeatedly turned to Tony Brown, a 4-year-old-boy found Sept. 25, 1969, hanging by a chain from the rafters of a Bergen Street garage. The case has haunted investigators for years. But Sabur and his partner, Detective Joseph Hadley, say they’ve gotten some fresh leads. So they’re going back at it.

They also re-opened the case of Joseph Policastro, who was found stabbed to death on Jan. 19, 1977 on Kossuth Street, a couple blocks from a bar he’d patronized. A relative of Policastro’s called Sabur and Hadley recently and gave them new information about the murder. The detectives went to the book, found the case number, and dug out the file.

The original investigation said Policastro had been killed outside. But there was blood found in the bar, and the bar was a popular hangout for people associated with organized crime - including, it seems, Policastro.

Now Sabur and Hadley think the killing was “a dump job,” meaning Policastro was killed in the bar, then dragged outside to die. And they’re zeroing in on a suspect.

NARRATIVE OF MURDERS

The “bible” - actually a large binder like the ones libraries use to fasten stacks of old newspapers - is showing its age. Some of the older pages break apart at the touch, and police officials are now laminating them.

Until 1967, when the FBI started the Uniform Crime Report to compile crime stats from around the country, the homicide book was the official source on the Newark homicide rate. The number of killings in Newark never really rose beyond 50 until the late 1960s. Then the murder rate started to soar. It rose above 160 a few times and bottomed out at 59 in 2000. Last year there were 97.

The thousands of entries form a loose narrative about how murder has changed in Newark. Since the 1930s, the ages of victims and suspects have gone down. And over time, as murders got more random, the number of cases with suspects decreased.

In the 1930s, blacks made up about half the victims and suspects. Nowadays, they make up the vast majority. Until 1958, they were labeled as “col,” for colored. Afterward, the police switched to “B.”

Guns have always been the weapon of choice for murderers, but killers in the old days used whatever was handy: ice picks, iron pipes, meat skewers, razors, baseball bats, pen knives, furniture, loaded hoses, glass pitchers, hatchets and flat irons.

Newark Police Director Anthony Ambrose, a former homicide detective, has paged through the book countless times. What strikes him is how the victims’ ethnicity changed with the city, but many of the homicide hot spots - Prince Street, Springfield Avenue, Grafton Avenue, for example - keep showing up.

“It’s amazing how the names have changed but the places stay the same,” Ambrose said.

SOURCE OF FAMILY HISTORY

The formula for recording cases hasn’t changed since detectives started the book in the early 20th century.

Because of this, it is easy to help citizens looking for information about long-dead loved ones.

Candace Gates contacted Newark police earlier this spring for help filling gaps in her family’s history.

Gates and her siblings knew their grandmother, Julia Everhart, was killed in Newark in the 1930s, but knew nothing else. Gates sent an e-mail to Capt. Derek Glenn in the police public information office, and Glenn went to the homicide book and found Everhart’s case. He jotted down the case number, dug out the corresponding file and went through the investigation reports. A week later, he got back in touch with Gates and gave her the story.

It went like this: Everhart, a mother of five children, lived in upstate New York with her family until she ran off with a man named John Talley, according to the homicide file. He took her to Newark, where they had a child together. But their relationship soured, and they had violent fights. On Dec. 3, 1932, Talley strangled and beat her to death. He went on the lam for a year before he was tracked down and confessed to Newark police.

“It’s a big relief in my heart to know the truth,” Gates said. “Now I can actually take a breath and say I know the details and explain them to my family.”

Police officer Hubert Henderson, who works with Glenn in the public information office, had never heard about the homicide book. But watching Glenn research the Everhart case opened the doors to his own personal discovery.

Henderson was 3 when his father, Fred, was stabbed to death in a Newark bar on Aug. 3, 1968. Four years later, a fire destroyed all the family’s belongings, including their pictures. So Henderson had no memory of his father or what he looked like. And his mother refused to talk about the case.

So Henderson found his father’s case number in the book and pulled his file, which included gruesome morgue photos and statements from witnesses. He learned his father was stabbed to death by a man who went berserk with a butcher knife inside the Jive Shack Tavern on 15th Avenue. The killer, James Green, was arrested a few days later.

Henderson was relieved to finally know the story. The pictures were ugly, but for the first time he had an image of his father’s face.

He spent a weekend quietly brooding over the new discovery before returning to work. The mystery was solved, and by Monday he was ready to move on.

“I’m satisfied,” Henderson said. “I’m also grateful. This is a part of my personal history that I never would have been able to access had it not been for that book.”